| Nautical

literature is bursting with the discussion of anchoring. It only takes

one incidence of dragging anchor in the middle of a dark night to understand

why the big deal. Even though we SWS sailors normally find a sheltered

bit of calm water to anchor for the night, it pays to anchor well, just in

case an unexpected storm comes through. There are two basic issues

here, what to anchor with, and how to anchor correctly. For SWSers there are four types of anchoring, 1) temporary anchoring “for lunch”, 2) anchoring for the night, 3) anchoring close to shore for a walk or talk with others, and 4) anchoring a raft of sailboats together for such purposes as passing the wine and cheese. |

| 6.7.1 Temperary Anchoring |

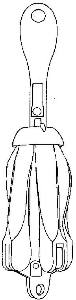

A light anchor can be used for a “lunch hook”. Select an anchor quite different from the main anchor. If the main anchor is good for sand and mud, then select a lunch hook that is good for rock, like a collapsible grapple with a short bit of chain and 100’ of line. For single handers it is convenient to have the anchor and line handy in the cockpit. Assure all forward movement of the boat has stopped and with a hand over hand movement plac  e the anchor on the bottom, assuring that chain is laid down clear of the

anchor itself. As the boat drifts back bring the line (that has been

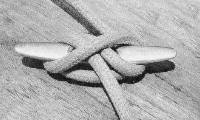

carefully flaked into a small bucket) forward and secure the rode with a round turn and a half-hitch on the bow

cleat, as pictured on the left. Assure that the boat’s drifting as stopped

and thereafter keep an eye out to assure the anchor holds. For temporary

anchorage a scope of 5 to 7 is generally acceptable.

e the anchor on the bottom, assuring that chain is laid down clear of the

anchor itself. As the boat drifts back bring the line (that has been

carefully flaked into a small bucket) forward and secure the rode with a round turn and a half-hitch on the bow

cleat, as pictured on the left. Assure that the boat’s drifting as stopped

and thereafter keep an eye out to assure the anchor holds. For temporary

anchorage a scope of 5 to 7 is generally acceptable.Collapsible Grapple Anchor

Rode = Rode is the length of anchor line and chain over the side and in the water. Scope = Scope is the rode divided by the sum of the water’s depth and the height of the anchor's cleat above the water. |

| 6.7.2 Anchoring for the Night |

| The main anchor needs

to be heavier and more substantial than the lunch hook. Two of the more

important anchor designs are discussed below; refer to the Reference Section

for books that go into more detail on the great variety of anchor types.

For SWSers, however, the two below are a good start. Once an anchor

is selected shackle an eight-foot length of chain to the anchor and add 150’

of 3/8” nylon line. The shackle pin should be wired to ensure it does

not loosen. The Danforth Anchor For a SWS type boat the Danforth anchor is in general use. It folds flat for storage, important in a small boat. It also offers tremendous holding power for its weight. The Danforth is an inexpensive anchor that digs in and holds well in sand and mud bottoms.

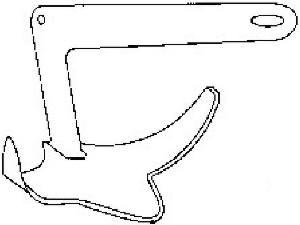

The Danforth was invented during WW II for use on seaplanes where high holding power and minimum weight were the goals. It meets these requirements admirably. However the Danforth has its drawbacks. It can be defeated by grass, gravel, hardpan, or rocky bottoms. It can be fowled by rubbish, rocks, or a poorly placed rode. When there’s a wind shift the anchor tends to flip over, as was intended by its designer, but sometimes its flukes get stuck pointing up and you drag. Actually I’ve used the Danforth as my main anchor on the Chesapeake, and have not had problems with it. But I am very careful to assure that it is dug in well and that I use a scope of 7 or more. I have not tested this anchor in other kinds of bottom other than the Chesapeake’s mud and sand. The Bruce Anchor

Although the Bruce anchor is horrid to stow, it’s compact compared with other anchors that do not collapse. It works well in the small sizes needed for a SWS. The long experience of the Dovekie fleet has proven that the Bruce is very unlikely to fowl, drag, or fail in any other way. It will tip itself upright on the first tug, and digs in and holds on the next, even with a relatively low scope. Backing down under power is generally unnecessary. Peter Duff loves this anchor and for this reason alone I finally got one to use as my main anchor. Main Anchor Techniques I use the same technique to drop the main anchor as the lunch hook. I bring the anchor (Bruce) and its pail of line out of the locker as I approach the anchorage. I determine which way the boat will lie to the anchor and make sure the boat begins to drift in that direction. I then hand over hand the anchor to the bottom and carefully place the chain away from the anchor so it does not become fouled. I then walk the pail up forward and allow about a scope of 10 and let the boat turn to the wind. I then pull hard to set the anchor. I do this twice. If I’m in a tight, protected spot I shorten the scope to about 7. With the Bruce you can chance an even shorter scope. I have also used the engine to dig the anchor in. This technique should be modified if the wind is strong. I would flake out the scope of eight in the cockpit then walk forward to secure the end of the rode to the bow cleat before getting to the anchorage. In that way when I place the anchor on the bottom I will not have to worry about dealing with a rode that is quickly snaking out of the boat. Some SWSers are in the habit of tying the end of the rode to a stern cleat, eliminating a trip to the bow and allowing the breeze to come over the stern. This can work fine provided you’re protected from wave action. If there is crew aboard, you probably will use the crew as anchorman. If so, discuss the anchoring routine beforehand. Discuss any hand or voice signals that would be used during any maneuvering. Try not to yell when there is a screw up. Remember, it’s the captain’s fault anyway for not providing a good anchoring drill beforehand. To prevent the rode and anchor from disappearing from sight, I tie the bitter end of the rode to the pail’s bail and have added a bit of foam floatation so if it all gets dumped overboard the pail will float (I am glad I did). |

| 6.7.3 Chafe, Rocks, and Tripping Line |

| Chafe should be prevented.

Chafe of the rode near the anchor is avoided by the use of chain, so sharp

objects on the bottom will not cut the rode. Chafe at the bow can be

eliminated by assuring the rode does not rub, and if it does to cover the

affected line with split garden hose or other such protection. A SWS will frequently anchor in shallow water and so you need to be aware of what’s on the bottom. To settle in mud is par for the course, but to settle on a pointed rock could spell disaster. Get out and walk your anchor around to a safe spot. The use of a tripping line with its bitter end attached to the eye at the bottom end of the anchor will allow a stuck anchor to be pulled clear. If you use a tripping line you will need a float at the working end and a way to adjust the length of free line so that the float stays on the surface near the anchor’s location. |